What is Art?

What is Art?

It is a skill that applies to music, painting, poetry, dance and more. Moreover, nature is no less than art. For instance, if nature creates something unique, it is also art. Artists use their artwork for passing along their feelings.

Thus, art and artists bring value to society and have been doing so throughout history. Art gives us an innovative way to view the world or society around us. Most important thing is that it lets us interpret it on our own individual experiences and associations.

Art is similar to live which has many definitions and examples. What is constant is that art is not perfect or does not revolve around perfection. It is something that continues growing and developing to express emotions, thoughts and human capacities.

Art comes in many different forms which include audios, visuals and more. Audios comprise songs, music, poems and more whereas visuals include painting, photography, movies and more.

You will notice that we consume a lot of audio art in the form of music, songs and more. It is because they help us to relax our mind. Moreover, it also has the ability to change our mood and brighten it up.

After that, it also motivates us and strengthens our emotions. Poetries are audio arts that help the author express their feelings in writings. We also have music that requires musical instruments to create a piece of art.

Other than that, visual arts help artists communicate with the viewer. It also allows the viewer to interpret the art in their own way. Thus, it invokes a variety of emotions among us. Thus, you see how essential art is for humankind.

Without art, the world would be a dull place. Take the recent pandemic, for example, it was not the sports or news which kept us entertained but the artists. Their work of arts in the form of shows, songs, music and more added meaning to our boring lives.

Therefore, art adds happiness and colours to our lives and save us from the boring monotony of daily life.

There is no one universal definition of visual art though there is a general consensus that art is the conscious creation of something beautiful or meaningful using skill and imagination. The definition and perceived value of works of art have changed throughout history and in different cultures. The Jean Basquiat painting that sold for $110.5 million at Sotheby’s auction in May 2017 would, no doubt, have had trouble finding an audience in Renaissance Italy, for example.1

Etymology

The term “art” is related to the Latin word “ars” meaning, art, skill, or craft. The first known use of the word comes from 13th-century manuscripts. However, the word art and its many variants (artem, eart, etc.) have probably existed since the founding of Rome.

Philosophy of Art

The definition of art has been debated for centuries among philosophers.”What is art?” is the most basic question in the philosophy of aesthetics, which really means, “How do we determine what is defined as art?” This implies two subtexts: the essential nature of art, and its social importance (or lack of it). The definition of art has generally fallen into three categories: representation, expression, and form.

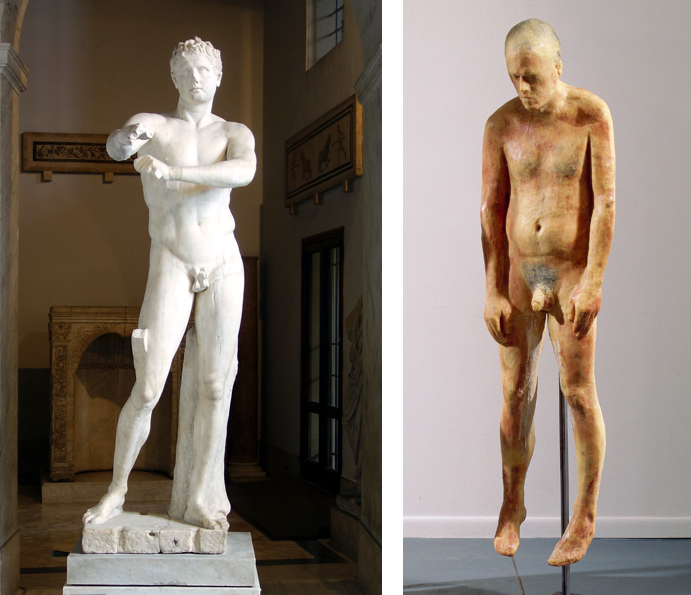

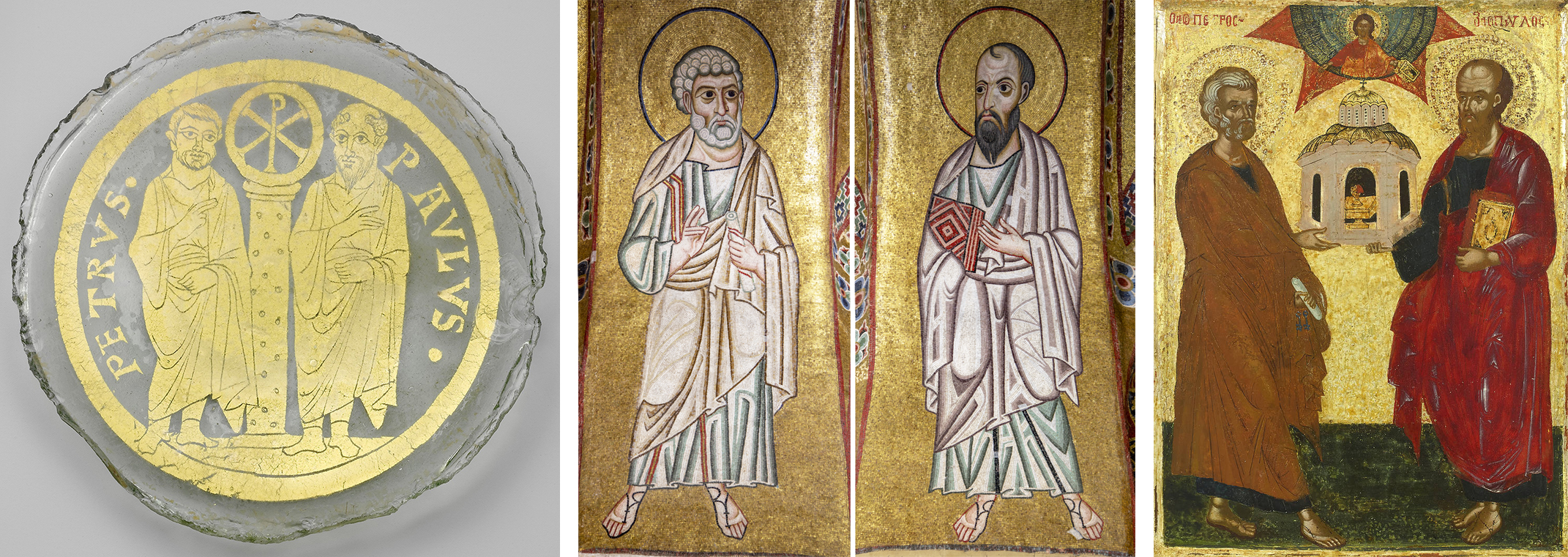

- Art as Representation or Mimesis. Plato first developed the idea of art as “mimesis,” which, in Greek, means copying or imitation. For this reason, the primary meaning of art was, for centuries, defined as the representation or replication of something that is beautiful or meaningful. Until roughly the end of the eighteenth century, a work of art was valued on the basis of how faithfully it replicated its subject. This definition of "good art" has had a profound impact on modern and contemporary artists; as Gordon Graham writes, “It leads people to place a high value on very lifelike portraits such as those by the great masters—Michelangelo, Rubens, Velásquez, and so on—and to raise questions about the value of ‘modern’ art—the cubist distortions of Picasso, the surrealist figures of Jan Miro, the abstracts of Kandinsky or the ‘action’ paintings of Jackson Pollock.” While representational art still exists today, it is no longer the only measure of value.

- Art as Expression of Emotional Content. Expression became important during the Romantic movement with artwork expressing a definite feeling, as in the sublime or dramatic. Audience response was important, for the artwork was intended to evoke an emotional response. This definition holds true today, as artists look to connect with and evoke responses from their viewers.

- Art as Form. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was one of the most influential of the early theorists toward the end of the 18th century. He believed that art should not have a concept but should be judged only on its formal qualities because the content of a work of art is not of aesthetic interest. Formal qualities became particularly important when art became more abstract in the 20th century, and the principles of art and design (balance, rhythm, harmony, unity) were used to define and assess art.

Today, all three modes of definition come into play in determining what is art, and its value, depending on the artwork being assessed.

History of How Art Is Defined

According to H.W Janson, author of the classic art textbook, The History of Art,“...we cannot escape viewing works of art in the context of time and circumstance, whether past or present. How indeed could it be otherwise, so long as art is still being created all around us, opening our eyes almost daily to new experiences and thus forcing us to adjust our sights?”

Throughout the centuries in Western culture from the 11th century on through the end of the 17th century, the definition of art was anything done with skill as the result of knowledge and practice. This meant that artists honed their craft, learning to replicate their subjects skillfully. The epitome of this occurred during the Dutch Golden Age when artists were free to paint in all sorts of different genres and made a living off their art in the robust economic and cultural climate of 17th century Netherlands.

During the Romantic period of the 18th century, as a reaction to the Enlightenment and its emphasis on science, empirical evidence, and rational thought, art began to be described as not just being something done with skill, but something that was also created in the pursuit of beauty and to express the artist’s emotions. Nature was glorified, and spirituality and free expression were celebrated. Artists, themselves, achieved a level of notoriety and were often guests of the aristocracy.

The Avant-garde art movement began in the 1850s with the realism of Gustave Courbet. It was followed by other modern art movements such as cubism, futurism, and surrealism, in which the artist pushed the boundaries of ideas and creativity. These represented innovative approaches to art-making and the definition of what is art expanded to include the idea of the originality of vision.

The idea of originality in art persists, leading to ever more genres and manifestations of art, such as digital art, performance art, conceptual art, environmental art, electronic art, etc.

Quotes

There are as many ways to define art as there are people in the universe, and each definition is influenced by the unique perspective of that person, as well as by their own personality and character. For example:

Rene Magritte

Art evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist.

Frank Lloyd Wright

Art is a discovery and development of elementary principles of nature into beautiful forms suitable for human use.

Thomas Merton

Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.

Pablo Picasso

The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca

All art is but imitation of nature.

Edgar Degas

Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.

Jean Sibelius

Art is the signature of civilizations.

Leo Tolstoy

Art is a human activity consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands-on to others feelings he has lived through, and that others are infected by these feelings and also experience them.

Conclusion

Today we consider the earliest symbolic scribblings of mankind to be art. As Chip Walter, of National Geographic, writes about these ancient paintings, “Their beauty whipsaws your sense of time. One moment you are anchored in the present, observing coolly. The next you are seeing the paintings as if all other art—all civilization—has yet to exist...creating a simple shape that stands for something else—a symbol, made by one mind, that can be shared with others—is obvious only after the fact. Even more than the cave art, these first concrete expressions of consciousness represent a leap from our animal past toward what we are today—a species awash in symbols, from the signs that guide your progress down the highway to the wedding ring on your finger and the icons on your iPhone.”

Archaeologist Nicholas Conard posited that the people who created these images “possessed minds as fully modern as ours and, like us, sought in ritual and myth answers to life’s mysteries, especially in the face of an uncertain world. Who governs the migration of the herds, grows the trees, shapes the moon, turns on the stars? Why must we die, and where do we go afterward? They wanted answers but they didn’t have any science-based explanations for the world around them.”

Art can be thought of as a symbol of what it means to be human, manifested in physical form for others to see and interpret. It can serve as a symbol for something that is tangible, or for a thought, an emotion, a feeling, or a concept. Through peaceful means, it can convey the full spectrum of the human experience. Perhaps that is why it is so important.

The word “art” is derived from the Latin ars, which originally meant “skill” or “craft.” These meanings are still primary in other English words derived from ars, such as “artifact” (a thing made by human skill) and “artisan” (a person skilled at making things). The meanings of “art” and “artist,” however, are not so straightforward. We understand art as involving more than just skilled craftsmanship. What exactly distinguishes a work of art from an artifact, or an artist from an artisan?

When asked this question, students typically come up with several ideas. One is beauty. Much art is visually striking, and in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, the analysis of aesthetic qualities was indeed central in art history. During this time, art that imitated ancient Greek and Roman art (the art of classical antiquity), was considered to embody a timeless perfection. Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a half, however, both art and art history have evolved radically.

Comments

Post a Comment